An American journalist based in Japan, Jake Adelstein has spent his life tracking the Yakuza, their networks, and their grey areas. In this interview, he looks back on his most significant investigations, his transition from journalism to private detective work, and the hidden side of Japanese organized crime – from cybercriminals to shell companies, and the fascinating phenomenon of the evaporated.

Read the interview in french :

Zone Critique : You’re an American from Missouri. You first became a journalist with the Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s largest daily newspaper. What drew you to this profession, in this country?

Jake Adelstein: Well, it wasn’t exactly a childhood dream to become a crime reporter in Japan. I studied Japanese in college, and when the opportunity to work for Yomiuri Shimbun came up, I took it. It was the largest newspaper in the country, and at the time, I was the first foreigner they had hired. It was a trial by fire, but I loved it. Journalism, especially covering crime, gave me an insider’s look into Japan’s underbelly – something most outsiders never see.

But let’s be honest, I was also an outsider fascinated by other outsiders. The Yakuza, despite being deeply Japanese, were made up of people on the fringes of society – Koreans, burakumin, and other marginalized groups. Their existence spoke to something deeper about Japanese society: the need for structure, even in crime, and how those cast out from the mainstream often found their own way to power.

It started as curiosity but became an obsession. There’s something about chasing stories, getting to the truth, and navigating the complex social dynamics of Japan that kept me going. Plus, Tokyo is a city where you can spend a lifetime and still never fully understand it. That mystery kept me hooked.

Zone Critique : In particular, you investigated one of the country’s most prominent Yakuza leaders, Tadamasa Goto. Your investigation contributed to his downfall. Could you tell us more about this case? Who was he, and what did your investigation reveal?

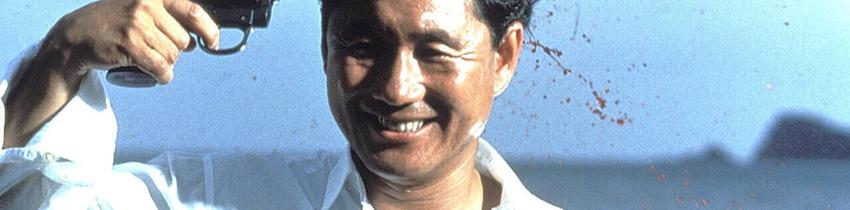

Jake Adelstein: Tadamasa Goto was the head of the Goto-gumi, a particularly violent faction of the Yamaguchi-gumi. He was ruthless – his group was known for extreme violence, including murders and assaults on journalists. What made him infamous wasn’t just his brutality but his deal with the FBI.

Goto and some of his men were given visas to enter the U.S. in exchange for providing intelligence on the Yakuza. He underwent a liver transplant at UCLA, essentially jumping the line while ordinary Americans died waiting.

When I found out about this, it was explosive. Here was one of Japan’s most dangerous crime bosses, cutting deals with the FBI while still running a criminal empire back home. My reporting on this led to a major scandal in Japan and eventually contributed to Goto’s downfall. He was forced out of the Yamaguchi-gumi in 2008 and later excommunicated entirely. He reinvented himself as a Buddhist priest, but let’s just say, not everyone buys the redemption arc.

It also revealed something deeper about the Yakuza: their ability to navigate international systems, whether it was exploiting weak regulations in Japan or cutting deals with American authorities to gain access to medical care.

Zone Critique : In Tokyo Vice (Marchialy editions), you talk about your life as a reporter, and in Tokyo Detective, you return to your second profession: that of private detective. Why did you decide to give up being a reporter to become a private detective?

Jake Adelstein: There were a few reasons. One is survival – literally. After exposing Goto, I was under threat. I had to be careful, and there were times when I genuinely feared for my life. Being a journalist in Japan covering organized crime is a high-risk job, and there were limits to what I could do within the press.

The other reason was curiosity. I wanted to keep investigating, but from a different angle. As a private investigator, I could go deeper into financial crimes, due diligence, and disappearances without the same constraints that come with working for a newspaper.

I also realized that the Yakuza weren’t the only ones with secrets. Japan has a whole industry around jōhatsu—people who choose to disappear. Whether it’s fleeing debts, abusive relationships, or societal pressure, they find ways to vanish. That world fascinated me, and it became a natural extension of my work.

Zone Critique : Are the two professions so different? Is your approach different as a private detective than as a journalist?

Jake Adelstein: There’s overlap, of course. Both require digging into people’s lives, asking uncomfortable questions, and piecing together information from various sources. But as a detective, you work more in the shadows. A journalist publishes their findings; a detective often keeps them confidential, sharing them only with a client.

It’s also a shift from informing the public to working behind the scenes. It means dealing with legal and ethical gray areas – what you can prove in court versus what you can print in a newspaper. The Yakuza understood this distinction too. As a reporter, they sometimes tolerated my presence. As a private investigator, they were much less forgiving.

Zone Critique : Has your work as a private detective enabled you to understand the sprawling world of the Yakuza better than your work as a journalist?

Jake Adelstein: Yes and no. As a journalist, I had access to law enforcement, the courts, and even some Yakuza members who were willing to talk off the record. As a detective, I saw more of the financial side – how they launder money, how they use front companies, and how they manipulate the system.

One of the biggest surprises was just how much of their power was bureaucratic. The Yakuza weren’t just gangsters with tattoos and missing fingers; they were deeply embedded in real estate, finance, and politics. They had lawyers, accountants, and front businesses that made them look legitimate. That level of sophistication is what has allowed them to survive despite crackdowns.

Zone Critique : Has the world of organized crime changed much since you began covering it in the 90s? What are the major changes?

Jake Adelstein: Absolutely. The Yakuza in the ‘90s were still operating openly, with office buildings and business cards. You could walk into a gang office and negotiate. Now, anti-Yakuza laws have pushed them underground. Membership has dropped from over 80,000 in the 1990s to about 12,000 today.

They’ve shifted away from traditional rackets and into cybercrime, fraud, and real estate scams. There are fewer gang wars, but the violence is still there – it’s just more strategic, less public. One of the biggest differences is that the Yakuza used to follow a certain code. Now, younger criminals don’t see the need for that structure.

There’s also the rise of tokuryū – loosely connected criminals who operate outside the Yakuza structure. They’re more fluid, harder to track, and often more ruthless because they don’t answer to a hierarchy.

Zone Critique : The world of the Yakuza is closely linked to the Kabukicho district. What was it like in the late 90s, and what is it like today?

Jake Adelstein: Kabukicho in the ‘90s was lawless in many ways – a red-light district with a visible Yakuza presence. Gangsters ran the bars, hostess clubs, and gambling dens. Police turned a blind eye as long as things didn’t get too messy.

Today, it’s been “cleaned up”, but that just means the crime has become more discreet. You don’t see Yakuza in suits standing outside clubs anymore, but the businesses are still connected to them in subtle ways.

Zone Critique : In Tokyo Detective, you talk about your due diligence investigative activity. What exactly does this mean?

Jake Adelstein: Due diligence is essentially corporate detective work. It’s investigating companies, individuals, or transactions to find hidden risks – whether that’s organized crime ties, financial fraud, corruption, or simply bad business practices. It’s often done for banks, corporations, or journalists working on big exposés.

One of the biggest surprises in this field was realizing just how much of Japan’s business world was, at some point, touched by Yakuza money. These groups didn’t just traffic drugs or run gambling dens – they were deeply involved in real estate, stock market manipulation, and corporate blackmail. A big part of my job as an investigator was tracing these connections and making sure companies weren’t getting into bed with people they’d regret doing business with.

Japan’s banking sector, in particular, has a long and complicated history with the Yakuza. For years, loans were handed out to gang-connected companies because banks either didn’t care or were afraid to say no. Even after legal crackdowns, some of these connections still linger in hidden ways.

Let me talk about one of the most important cases I worked on. I warned my client to stay away from the company and they didn’t listen much to their regret. The Suruga Corporation case was a classic example of how the Yakuza, real estate, and corporate Japan intertwined in a way that left everyone just enough plausible deniability to avoid serious punishment – until the whole thing unraveled in 2008.

Suruga Corporation was a successful real estate firm, generating $300 million a year and listed on the second section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. But success in the real estate business in Japan often means dealing with “problematic tenants” – people who refuse to leave properties developers want to raze. Enter the Yamaguchi-gumi, Japan’s largest Yakuza syndicate, working through a front company. Instead of negotiating the legal way, Suruga paid more than $100 million over several years to a Goto-gumi front company Koyojitsugyo to ‘persuade’ tenants to move out.

Now, “persuasion” in this case meant textbook land-sharking (jīage) – a specialty of the Yakuza. Bar owners and residents found themselves harassed, intimidated, and driven out. One Setagaya bar owner saw Yakuza thugs sitting in her bar for hours, glaring at customers, rolling up sleeves to flash tattoos – just enough menace to drive business away without crossing the line into something that would get police attention. Fake health notices were posted outsi...