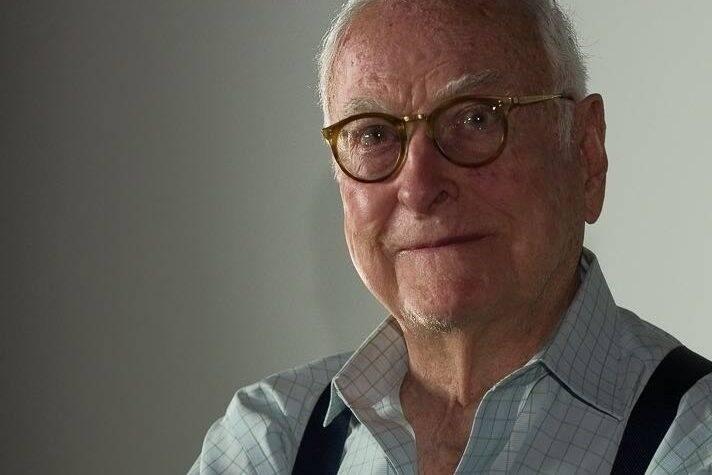

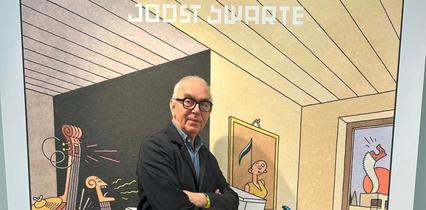

Seize ans après son dernier film, City of your Final Destination, James Ivory, 95 ans, le légendaire réalisateur des Vestiges du jour, Retour à Howards End ou bien encore des Bostoniennes, revient sur le grand écran avec Un Été afghan (A Cooler Climate), qu’il a co-réalisé avec Giles Gardner. Bien différent de ses adaptations de Henry James, Kazuo Ishiguro ou d’E.M. Forster (même si ce dernier est toujours bien présent), Un Été afghan est un film monté à partir d’un documentaire inachevé qu’Ivory avait tourné en Afghanistan en 1960. Sur la base de ces images d’archives, le cinéaste a élaboré un long métrage autobiographique mêlant les repères temporels et spatiaux : l’Afghanistan du XVIe siècle, celui de 1960, l’Oregon des années cinquante et le temps présent.

Le spectateur retrouve, dans ce film où l’émotion est le maître-mot, les prémices de la fructueuse collaboration avec Ismail Merchant, producteur et compagnon d’Ivory, et Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, la romancière et scénariste attitrée du duo. Il prend aussi connaissance des débuts de la vocation de cinéaste d’Ivory, alors que ce dernier est encore un adolescent timide et complexé contraint de dissimuler ses penchants homosexuels à une époque où cela était toujours mal vu. Enfin, sur une musique tout en retenue d’Alexandre Desplat, le film suit sa narration déstructurée, guidé par de mélancoliques extraits des mémoires de l’empereur moghol Babur.

Ode aux voyages, à la découverte de l’inconnu et à l’émerveillement qui s’ensuit, Un Été afghan est également une œuvre sensible sur l’initiation à la vie et aux sentiments amoureux de deux jeunes hommes à cinq siècles de distance.

Zone Critique : Vous avez retrouvé dans vos archives un film documentaire inachevé réalisé en 1960. Pouvez-vous revenir sur la genèse de ce film et dire quelles sont les raisons pour lesquelles vous avez choisi de retravailler dessus soixante ans plus tard ?

James Ivory : A l’origine, j��’avais été envoyé en Inde par the Asia Society of New York, qui m’avait attribué une bourse pour réaliser un documentaire, une sorte de portrait historique de la ville de Delhi, qui sera plus tard The Delhi Way. J’ai commencé à le tourner, mais il faisait une chaleur épouvantable à Delhi, c’était vraiment insupportable. Je n’en pouvais plus ; je l’ai fait savoir à mon équipe de production et les commanditaires du film qui m’avaient envoyé là-bas m’ont dit : « Eh bien, rends-toi dans un pays voisin où il fait moins chaud et tourne quelque chose là-bas en attendant. Quand le climat se sera rafraîchi en Inde, tu reviendras. » Le seul pays à proximité où il faisait plus frais était l’Afghanistan, qui se trouve à une heure d’avion de Delhi environ. Je me suis donc rendu à Kaboul. Mais je ne connaissais rien du tout de l’Afghanistan. Je ne m’étais pas du tout préparé, je ne savais même pas que c’était un pays musulman et qu’il y avait encore un roi vivant dans un palais ! Tout était nouveau pour moi ; quelques officiels ont été envoyés par le gouvernement pour m’aider à m’orienter. On m’a attaché les services d’un accompagnateur qui devait s’assurer que je ne filme pas tout et n’importe quoi car ils voulaient garder secrètes certaines facettes de cette société qui commençait à s’ouvrir au monde et qui empruntait la voie de la modernité. J’y ai passé tout l’été et j’ai tourné environ trois mille mètres de bobine 16 mm. Je suis ensuite retourné en Inde et j’ai terminé le tournage du premier film, puis je suis rentré à New York.

La tâche suivante consistait à monter le film indien. Je n’avais pas le temps de penser au film afghan. J’avais envoyé les pellicules à un laboratoire, elles avaient toutes été développées, mais j’étais dans l’incapacité de m’y consacrer dans un futur proche. Alors que je mettais la dernière main à mon film indien, j’ai rencontré Ismail Merchant à New York, qui était sur le point de retourner à Bombay où il vivait. J’ai décidé de l’accompagner car il me manquait quelques scènes supplémentaires à tourner et j’ai pu procéder ainsi au tournage additionnel. C’est alors, une fois de retour aux Etats-Unis, qu’Ismail a exprimé le désir de travailler sur son premier long métrage. On lui avait offert le roman The Householder, de Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, et il m’a conseillé de le lire. Il venait tout juste d’être nommé aux Oscars (dans la sélection de l’Oscar du court métrage en prise de vue réelle) pour le film court qu’il avait réalisé, La Création de la femme, et il avait dû se rendre à Hollywood. Il m’a alors dit : « À Hollywood, ils ne réaliseront jamais ce film, pourquoi ne pas t’en charger ? Faisons-le ensemble ! » Mais je n’avais jamais réalisé de long métrage, il m’a alors répondu : « Moi non plus, je n’en ai jamais produit ! » ; nous sommes allés voir Ruth et elle nous a dit la même chose : elle n’avait jamais écrit de scénario ! Nous nous sommes mis à l’ouvrage et l’avons finalement réalisé, contre toute attente. C’était notre première collaboration à trois, ce qu’Ismail Merchant a appelé plus tard le monstre tricéphale.

Le film afghan a été mis de côté définitivement. Je l’ai conservé pendant soixante ans près de moi, dans un endroit d’où je pouvais le sortir et le montrer à des amis et connaissances.

Le film afghan a été mis de côté définitivement. Je l’ai conservé pendant soixante ans près de moi, dans un endroit d’où je pouvais le sortir et le montrer à des amis et connaissances. J’avais un projecteur 16 mm pour cela. Il était en bon état, protégé dans mon laboratoire, dans une grande boîte en carton. D’abord dans mon appartement de New York, puis dans ma maison de la vallée de l’Hudson. Je ne l’avais donc pas oublié ; je dirais même plus : je l’aimais beaucoup et je le trouvais très intéressant. Mais la vie m’a conduit à des projets différents et j’ai réalisé d’autres films dans l’intervalle, les uns après les autres, pendant plus de quarante ans. C’est pour cela que je ne suis jamais revenu dessus. Maintenant que je ne suis plus aussi actif, j’ai pu me replonger dans ces archives et j’ai décidé d’en faire un film, en collaboration avec Giles Gardner avec qui je l’ai écrit. C’est ainsi qu’il est né. J’ai parlé du temps qu’il faisait à Kaboul, c’est ce qui a donné son titre au film, A Cooler Climate, qui est également un clin d’œil à l’un des livres de Ruth, A Stronger Climate.

ZC : Comment votre amitié avec Giles Gardner est-elle née et comment s’est déroulée la co-réalisation avec lui ?

JI : Très bien ! Nous avions la même vision et sa contribution a été d’une grande aide pour l’écriture du film. Par exemple, je n’avais pas eu l’idée de structurer le film de cette manière. Tout cela est apparu récemment. La structure, la tournure et la partie biographique sont le fruit des trois dernières années et le résultat de mes dialogues avec Giles. Je l’ai rencontré sur le plateau d’un de nos précédents films. Il a été mon assistant. Puis il a travaillé au département du son. C’est ainsi que je l’ai connu. A l’époque, il vivait en Angleterre. Aujourd’hui, il vit en France.

ZC : Le résultat final s’éloigne du projet que vous aviez initié puisqu’il est devenu un film autobiographique. Dans quelle mesure ce film et votre séjour de presque un an en Asie, où vous avez filmé également en Inde, ont influé sur votre carrière cinématographique ?

JI : Ils ont eu un énorme impact. Je ne dirais pas nécessairement que j’ai été « influencé » par l’Inde, sa culture, ses pensées ou sa religion. Ce genre de choses ne m’intéressaient pas vraiment. Mais j’ai réalisé mes quatre premiers longs métrages en Inde. Mon deuxième film, Shakespeare Wallah, a connu un tel succès que la Twentieth Century Fox a décidé de financer et de distribuer mon troisième, Le Gourou. Après ces quatre films, j’en ai fait deux autres bien plus tard qui avaient aussi l’Inde pour sujet : Autobiographie d’une princesse et Chaleur et Poussière. C’était très important pour moi, émotionnellement, c’était l’endroit où il fallait être. J’ai adoré séjourner en Inde, j’aimais beaucoup les Indiens, nous nous entendions tous très bien. Mais je ne saurais dire si cela a réellement influencé mes films, hormis en ce qui concerne l’histoire, la musique, les localités, les acteurs etc.

ZC : Vous dites, dans Un Été afghan, que vous avez eu l’idée du film indien après avoir vu par hasard des miniatures indiennes chez un collectionneur. Devez-vous votre carrière à une série de petites coïncidences ?

JI : Je pense que oui. C’était un hasard extraordinaire. Un jour, je me suis rendu chez un antiquaire, à San Francisco, pour voir ses estampes de Canaletto. En entrant dans sa galerie, j’ai remarqué des miniatures indiennes et perses que quelqu’un avait consultées et étalées sur la table. Il n’avait pas eu le temps de les ranger et il y en avait partout. C’est comme cela que mon intérêt s’est révélé. Plus tard, je me suis demandé : et si cette personne avait eu le temps de ranger les miniatures ? Les aurais-je vues malgré tout ? Sinon, aurais-je fait la carrière que j’ai faite ? Je n’ai pas la réponse. Je ne serais peut-être jamais parti en Inde, mon film n’aurait pas vu le jour et je n’aurais pas rencontré Ismail Merchant. C’était en tout cas un heureux accident.

ZC : Vous apparaissez, en tant que protagoniste du film, même si vous ne parlez pas devant la caméra. S’agissait-il d’une première pour vous ?

JI : J’avais déjà été filmé auparavant, pour de la publicité, des bonus de DVD, à la télévision, etc. Mais je n’avais jamais fait de films en tant que tel. C’était une expérience un peu étrange. On doit rester tel que l’on est dans la vie quotidienne, on ne peut pas jouer de rôle, alors on fait avec.

ZC : Vous filmez un Afghanistan qui n’a pas encore connu l’invasion soviétique ni la prise de pouvoir des talibans. Vous montrez un pays très traditionnel qui commence à s’ouvrir au progrès et à s’occidentaliser. Mais les résistances persistent, notamment dans les campagnes. Vous aviez perçu ce tiraillement mais les autorités ne vous permettaient pas de filmer ce qui pouvait paraître comme un reliquat du passé. Avez-vous eu l’impression d’enfreindre souvent les règles ? Cela comportait-il des risques ?

JI : La plupart du temps, ils ne se souciaient pas de ce que je faisais. Je pouvais filmer ce que je voulais. Mais il y avait un blocage sur certains aspects de la société, qu’ils ne voulaient pas que je filme parce qu’ils estimaient que cela ne devait plus exister. Et s’ils décidaient que cela ne devait plus exister, alors cela n’existait plus pour de bon. L’un de ces points de discorde concernait les femmes qui portaient de longs voiles, couvrant tout leur corps. Le gouvernement avait interdit le port de ces voiles intégraux. La règle était suivie par certaines femmes dans les grandes villes et complètement ignorée dans les campagnes où les maris obligeaient leurs épouses à le porter. Je savais qu’elles n’aimaient pas ça et qu’elles ne voulaient pas que je filme, mais je ne savais pas comment l’éviter, car il s’agissait de scènes de rue où il y avait du monde. Mais finalement, cela me plaisait plutôt bien. Comme je l’ai dit dans le film, il est plus intéressant et plus cinématographique de montrer à l’écran des femmes avec ces longs voiles orientaux. Nous étions en présence de deux modes de vie qui ne se comprenaient pas. Les Afghans essayaient de devenir aussi modernes que possible, mais il leur restait encore beaucoup de chemin à parcourir.

En ce qui concerne les risques, si les autorités étaient venues me voir en me disant « ne filmez pas ça ! », je ne l’aurais pas fait, cela m’aurait fourni une excuse. Je dépendais d’eux comme ils dépendaient de moi. Ils voulaient que je suive les règles et, dans l’ensemble, je les ai respectées. Il n’y a qu’une ou deux choses qui ne leur ont pas plu et qui, à mon sens, n’étaient pas très importantes. Par exemple, j’ai filmé de jeunes garçons jouant avec des têtes de chèvre dans la rivière. Je ne voyais pas ce qu’il y avait de si terrible là-dedans et je ne comprenais pas pourquoi je ne devais pas montrer cela. La démolition de la mosquée, qui étaient en ruines, était également un point sensible : ils la détruisaient pour pouvoir en construire une nouvelle, plus grande. Les Afghans m’ont défendu de filmer cela pour ne pas donner l’occasion au Pakistan, leur grand ennemi, de dire : « Vous voyez, ils démolissent des mosquées, ce ne sont pas de bons musulmans, ce sont des infidèles. » J’ai malgré tout filmé en secret. Certes, je n’aurais pas dû, mais je l’ai quand même fait et j’en suis heureux car cela a donné de très belles images.

ZC : Vous faites part de votre déception de ne pas avoir pu trouver de patrimoine historique à Kaboul, ni de monuments, hormis les statues des Bouddhas de Bamiyan. Cela n’a-t-il pas été plutôt bénéfique, car vous vous êtes focalisé sur la population ?

JI : Il n’y avait rien du tout ! Mais même lorsque j’étais en Inde, je me suis concentré sur les gens et leurs activités, alors qu’il y a pléthore de bâtiments magnifiques à Delhi. Mais en Afghanistan, rien de tel. C’était assez frustrant de ce point de vue-là. Je me suis donc « raccroché » si j’ose dire aux statues des Bouddhas. Je ne pouvais pas prévoir que ces sculptures millénaires seraient détruites quarante ans plus tard. C’est très émouvant rétrospectivement.

ZC : Tout au long du film, le spectateur est guidé par l’empereur moghol Babur, qui a conquis l’Afghanistan au XVIe siècle et sur les mémoires duquel vous vous appuyez pour illustrer vos propos et vos images. Vous le montrez comme un personnage sensible, attachant, presque fragile. Avez-vous senti une certaine proximité avec lui, notamment dans les sentiments qu’il a éprouvés pour un jeune Afghan, Baburi ?

JI : Pas fragile, non, je ne dirais pas cela. Babur a fondé son empire dès l’âge de quatorze ans. À dix-sept ou dix-huit ans, donc très jeune, il avait déjà envahi et conquis l’Inde. Il est alors devenu le premier empereur moghol. Il s’est aussi rendu en Afghanistan, qu’il a annexé. Et pendant tout ce temps, il écrivait ses mémoires, sans doute les premiers écrits autobiographiques de l’Histoire, qui décrivent ses pensées, ses états d’âme, ses espoirs, ses regrets… Il n’aurait jamais imaginé qu’une telle œuvre puisse être un jour publiée et lue par le grand public, mais c’est pourtant ce qu’il s’est passé. Au fur et à mesure qu’il vieillissait, ses écrits devenaient moins personnels ; en effet, y figuraient davantage de récits de batailles, de conquêtes de nouveaux territoires et de raisonnements politiques. Je ressens une certaine empathie pour lui, peut-être en particulier au regard des sentiments qu’il a éprouvés pour ce Baburi, dont le nom était curieusement similaire au sien. Au moment du tournage, je n’étais pas au courant de tout ce contexte. Je n’avais pas lu ses mémoires. Je ne l’ai su que bien après, et même tout récemment. J’ai découvert alors un homme sensible, qui avait le mal du pays et qui souffrait de mélancolie. Il aimait beaucoup l’Afghanistan et Kaboul, comme on peut le voir dans le film. Par exemple, lorsqu’on lui a apporté un melon d’Afghanistan pour le réconforter, il a pleuré car cela lui rappelait trop ses jours heureux. C’est quelque chose de très émouvant.

ZC : Le voyage donne du sens à la vie, pour Babur. Pour vous également car vous vous êtes ouvert à de nouvelles cultures en Asie et vous avez traversé la moitié du monde pour filmer. S’agit-il d’un récit d’initiation parallèle, à cinq siècles de distance ?

C’est le premier grand voyage que j’ai effectué et il a changé ma façon de voir les choses, toutes mes certitudes.

JI : Comme Babur lui-même le dit, il faut sortir de sa zone de confort et faire quelque chose de sa vie. C’est ainsi que l’on devient quelqu’un. Cette réflexion est toujours vraie. Je devais aller en Afghanistan, pour me découvrir et savoir qui j’étais. C’est le premier grand voyage que j’ai effectué et il a changé ma façon de voir les choses, toutes mes certitudes. Cela m’a donné le goût des grandes excursions et j’ai beaucoup voyagé par la suite, y compris à Paris !

ZC : Une initiation également au sentiment amoureux, mais aussi à l’interdit et à l’exclusion, en raison de votre homosexualité. Dans les années cinquante, vous ne pouviez pas afficher ouvertement vos sentiments pour votre camarade de lycée. Babur a peut-être réprimé sa vraie nature, comme vous au lycée, ainsi que vous le montrez dans le film.

JI : Je ne pense pas qu’il y ait eu cette nature en lui. Comme il l’a dit, il n’avait jamais ressenti de désir pour qui que ce soit, y compris son épouse, avant de rencontrer ce jeune garçon. Il ne savait donc pas qu’il était pourvu de cette capacité à ressentir un sentiment amoureux. Mais je ne parlerais pas pour autant de nature refoulée, car c’est une idée moderne. Je préfère évoquer un sentiment d’attirance envers une autre personne, qui s’est matérialisé.

ZC : Une autre figure récurrente dans votre cinéma, en plus de Merchant et Jhabvala, c’est E.M. Forster, une de vos sources d’inspiration principales et qu’on retrouve ici. Dans quelle mesure vous a-t-il fait découvrir Kaboul et peut-on dire que c’est aussi par la littérature que vous êtes devenu cinéaste ?

JI : Non, j’étais cinéaste bien avant cela. Il avait écrit un roman très célèbre sur l’Inde, intitulé Route des Indes (Passage to India). J’ai lu ce roman aussitôt que je me suis intéressé à l’Inde. C’est par ce biais que j’ai connu E.M. Forster. Mais son œuvre n’avait pas d’importance particulière pour moi à l’époque ; je ne connaissais pas ses autres romans et ils ne m’intéressaient pas plus que cela. Ce n’est que bien plus tard que j’ai été sensibilisé à sa littérature grâce à Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, dont Forster était l’écrivain préféré et dont elle adorait les écrits. C’est alors que j’ai commencé à me plonger dans les autres romans, que j’ai par la suite adaptés : Chambre avec vue, Howards End, Maurice…

Je vais vous raconter une anecdote, que je ne partage pas souvent. De nombreux cinéastes souhaitaient adapter Route des Indes à l’écran et ils ont demandé à Forster s’ils pouvaient obtenir les droits du roman, y compris le grand réalisateur indien Satyajit Ray. Ce dernier a rendu visite au romancier à Cambridge ; il avait apporté ses films pour lui montrer ses talents. Forster les a fortement appréciés et tous deux se sont bien entendus, mais finalement, il a pris la décision de ne pas céder les droits, du moins de son vivant. Ray est donc retourné en Inde et n’a jamais réalisé le film. Après la mort de Forster, Ismail Merchant et moi-même avons été approchés par le King’s College, qui était le légataire et l’exécuteur testamentaire de Forster. Les représentants de King’s nous ont alors invités à leur rendre visite à Cambridge. Nous savions très bien ce qu’ils comptaient nous proposer : une adaptation de Route des Indes. C’est ce qui s’est produit ; dès notre arrivée, ils nous ont offert les droits. Mais nous avons refusé car nous avions de nombreux autres projets en attente et nous leur avons répondu que ce que nous souhaiterions vraiment tourner, c’est Chambre avec vue, un autre roman de Forster. Ils étaient interloqués : « Comment cela ? Chambre avec vue ? Ce petit roman comique ? Vous préférez adapter ça plutôt que le grand classique Route des Indes ? » Nous avons confirmé notre choix et ils ont fini par nous donner les droits. Nous avons eu par la suite affaire à eux à deux autres reprises : pour l’adaptation de Maurice et enfin, en 1991, Howards End.

ZC : Et Route des Indes a finalement été adapté par David Lean en 1984. Il a d’ailleurs été son dernier film. Qu’en avez-vous pensé ?

JI : Je ne l’ai pas aimé, pas plus que je n’ai apprécié la personnalité de David Lean lui-même, que j’ai rencontré à plusieurs reprises, en Inde et ailleurs. Il était exactement ce genre d’Anglais que Forster détestait : il trépignait, criait… Il représentait aussi ce genre d’hommes dont Forster estimait qu’ils n’auraient jamais dû s’impliquer en Inde, sous peine de commettre des erreurs terribles. On voit ces individus dans les romans de Forster, comme Howards End. L’un des personnages de mon film, M. Wilcox, joué par Anthony Hopkins, aurait pu être Lean. Ou plus exactement, David Lean aurait pu incarner M. Wilcox à la perfection. Lean et Forster n’étaient donc pas des personnes destinées à s’entendre et adopter une même vision des choses. Ils étaient même plutôt radicalement opposés.

ZC : D’ailleurs, lui aussi a réalisé un film sur Venise, contemporain du vôtre, mais qui est une fiction : Vacances à Venise.

Si l’on parvient à restituer un plus beau résultat en trichant un peu avec la réalité, où est le mal ? Vous laissez libre cours à votre imagination et à votre sens de la beauté et de l’esthétique. Cela relève de la liberté de l’artiste.

JI : Celui-là, pour le coup, je l’ai plutôt bien apprécié. J’ai réalisé mon film sur Venise en 1953 et lui le sien en 1955. J’étais particulièrement content de voir Venise filmée sous cet angle, même si, à l’époque, certains éléments, que je trouvais erronés, m’avaient heurté, comme la disposition des bâtiments le long du Grand Canal, qu’on voit dans son film depuis une gondole. Il avait, au montage, complètement modifié l’aspect de la ville en montrant tel édifice qui n’aurait jamais dû être là. J’ai trouvé cela malhonnête. Si vous filmez Venise, ou une autre ville qui existe bel et bien, vous avez comme devoir de la photographier exactement telle que vous la voyez, sans rien y changer, sinon elle perd en authenticité. C’était ma façon de penser et de concevoir un film à l’époque. Cela dit, avec l’âge, j’ai dû me résoudre à reproduire exactement le même travers que je critiquais quelques années avant, en grande partie pour des raisons esthétiques et pratiques. Si l’on parvient à restituer un plus beau résultat en trichant un peu avec la réalité, où est le mal ? Vous laissez libre cours à votre imagination et à votre sens de la beauté et de l’esthétique. Cela relève de la liberté de l’artiste.

ZC : Vous avez réalisé de nombreux films sur la société britannique du XXe siècle, notamment à l’époque d’Edouard VII. On a pu vous prendre à tort pour un cinéaste britannique ; or, vous êtes américain et vous le rappelez bien ici. Quel rapport entretenez-vous avec votre pays natal ?

JI : J’ai réalisé de nombreux films typiquement américains, nonobstant. J’ai toujours vécu en Amérique, jamais à l’étranger, sauf en tournage, que ce soit à Paris pendant un certain temps, ou à Londres, en Inde, en Amérique du Sud, en Chine, etc. Mais j’ai toujours fini par revenir chez moi, à New York. Je ne me suis jamais senti expatrié en Amérique. Natif de Californie, j’ai déménagé très jeune dans l’Oregon avec ma famille. J’étais à cette époque le petit garçon que vous voyez dans le film. J’y ai passé mon enfance et mon adolescence, puis je suis parti à l’université et j’ai suivi de nouveau ma famille en Californie. D’ailleurs, comme je le signale dans le film, certains paysages d’Afghanistan me rappelaient ceux qu’on peut admirer en Arizona ou dans le Colorado, du fait de leur topographie similaire et parce qu’ils sont de la même couleur rouge. Signe que je n’ai jamais vraiment quitté l’Amérique.

ZC : Pour conclure, avez-vous encore d’autres films cachés dans vos archives qu’on pourrait un jour redécouvrir ?

JI : Non, c’est fini, il n’y en a plus. J’ai beaucoup aimé monter ce film. C’était une expérience très amusante. Je ne savais pas vraiment ce que Giles préparait : il avait beaucoup de choses en tête sur ce qu’il allait faire dont je n’étais pas au courant au départ. Et petit à petit, tout s’est mis en place. Mais maintenant, je n’ai pas vraiment d’autres projets, je suis trop âgé. Peut-être des mémoires ? Qui sait…

***

James Ivory : “A Cooler Climate is the result of a happy accident”

Sixteen years after his last film, City of your Final Destination, James Ivory, 95, the legendary director of The Remains of the Day, Return to Howards End and The Bostonians, returns to the big screen with A Cooler Climate, which he co-directed with Giles Gardner. Quite different from his adaptations of Henry James, Kazuo Ishiguro or E.M. Forster (although the latter is still very much in evidence), A Cooler Climate is a film based on an unfinished documentary that Ivory filmed in Afghanistan in 1960. On the basis of this archive footage, the filmmaker created an autobiographical feature that blends temporal and spatial references: Afghanistan in the 16th century, Afghanistan in 1960, Oregon in the 1950s and the present day. In this film, where emotion is the key word, the viewer encounters the beginnings of the fruitful collaboration with Ismail Merchant, Ivory’s producer and companion, and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, the duo’s regular novelist and screenwriter. He also learns about the beginnings of Ivory’s vocation as a filmmaker, when he was still a shy, self-conscious teenager forced to conceal his homosexual inclinations at a time when this was still frowned upon. Finally, set to a restrained score by Alexandre Desplat, the film follows its unstructured narrative, guided by melancholy extracts from the memoirs of the Mughal emperor Babur. An ode to travel, the discovery of the unknown and the wonder that follows, A Cooler Climate is also a sensitive work about two young men’s initiation into life and their feelings of love five centuries apart.

- In your archives, you found an unfinished documentary film made in 1960. Can you go back over the genesis of this film and explain why you chose to work on it again sixty years later?

I was originally sent to India by the Asia Society of New York, which awarded me a grant to make a documentary, a kind of historical portrait of the city of Delhi, which later became The Delhi Way. I started shooting it, but it was terribly hot in Delhi, really unbearable. I couldn’t take it any more; I told my production team and the film’s sponsors who had sent me there said: “Well, go to a neighbouring country where it’s not so hot and shoot something there in the meantime. When the weather cools down in India, you can come back.” The only nearby country where it was cooler was Afghanistan, which is about an hour’s flight from Delhi. So I went to Kabul. But I knew nothing at all about Afghanistan. I hadn’t prepared myself at all; I didn’t even know that it was a Muslim country and that there was still a king living in a palace! Everything was new to me; a few officials were sent by the government to help me get my bearings. I was assigned an escort who had to make sure that I didn’t film everything and anything, because they wanted to keep certain aspects of this society, which was beginning to open up to the world and move towards modernity, secret. I spent the whole summer there and shot about ten thousands ft of 16 mm film. I then went back to India and finished shooting the first film, then returned to New York.

The next task was to edit the Indian film. I didn’t have time to think about the Afghan film. I’d sent the films to a lab and they’d all been developed, but I couldn’t devote any time to it in the near future. While I was putting the finishing touches to my Indian film, I met Ismail Merchant in New York, who was about to return to Bombay where he lived. I decided to go with him as I was short of a few more scenes to shoot and was able to proceed with the additional filming. It was then, back in the States, that Ismail expressed a desire to work on his first feature film. He had been offered the novel The Householder, by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, and he advised me to read it. He had just been nominated for an Oscar (the Academy Award for Live Action Short Film) for the short film he had made, The Creation of Woman, and he had had to go to Hollywood. He said to me: “In Hollywood, they’ll never make this film, so why don’t you do it? Let’s do it together!” We went to see Ruth and she told us the same thing: she’d never written a screenplay! We got down to work and finally produced it, against all the odds. It was our first three-way collaboration, what Ismail Merchant later called the three-headed monster.

The Afghan film was put aside for good. I kept it close to me for sixty years, in a place where I could take it out and show it to friends and acquaintances. I had a 16mm projector for that. It was in good condition, protected in my laboratory, in a large cardboard box. First in my flat in New York, then in my house in the Hudson Valley. So I hadn’t forgotten about it; I’d even go so far as to say that I liked it very much and found it very interesting. But life led me to different projects and I made other films in between, one after the other after the other, for more than forty years. That’s why I’ve never gone back to it. Now that I’m not so active, I’ve been able to delve back into these archives and I’ve decided to make a film about them, in collaboration with Giles Gardner, with whom I wrote it. That’s how it came about. I talked about the weather in Kabul, and that’s what gave the film its title, A Cooler Climate, which is also a reference to one of Ruth’s books, A Stronger Climate.

- How did your friendship with Giles Gardner come about and how did co-directing with him go?

Very well! We had the same vision and his contribution was a great help in writing the film. For example, I hadn’t had the idea of structuring the film in this way. It all came together recently. The structure and the biographical part are the fruit of the last three years and the result of my dialogues with Giles. I met him on the set of one of our previous films. He was my assistant. Then he worked in the sound department. That’s how I got to know him. At the time, he was living in England. Now he lives in France.

- The end result is a far cry from the project you started, as it has become an autobiographical film. To what extent did this film and your almost year-long stay in Asia, where you also filmed in India, influence your film career?

Hugely. I wouldn’t necessarily say that I was ‘influenced’ by India, its culture, its thoughts or its religion. I wasn’t really interested in that sort of thing. But I made my first four feature films in India. My second film, Shakespeare Wallah, was so successful that Twentieth Century Fox decided to finance and distribute my third, The Guru. After these four films, I made two others much later that also had India as their subject: Autobiography of a Princess and Heat and Dust. It was very important for me, emotionally, it was the place to be. I loved being in India, I loved the Indian people, we all got on really well. But I can’t say whether it really influenced my films, apart from the history, the music, the places, the actors and so on.

- You say, in A Cooler Climate, that you had the idea to shoot to India after seeing some Indian miniatures by chance in a collector’s shop. Do you owe your career to a series of small coincidences?

I think so. It was an extraordinary coincidence. One day, I went to an antique dealer in San Francisco to see his Canaletto prints. As I entered his gallery, I noticed some Indian and Persian miniatures that someone had been looking at and had spread out on the table. He hadn’t had time to put them away and they were everywhere. That’s how my interest was piqued. Later, I asked myself: what if that person had had time to put the miniatures away? Would I still have seen them? If not, would I have made the career I did? I don’t know. I might never have gone to India, my film might never have seen the light of day and I might never have met Ismail Merchant. In any case, it was a happy accident.

- You appear as the film’s protagonist, even if you don’t speak on camera. Was this your first time in front of the camera?

I’d been filmed before, for advertising, DVD extras, television and so on. But I’d never made a film as such. It was a rather odd experience. You have to stay as you are in everyday life, you can’t play a role, so you just go with it.

- As you point out, you are filming an Afghanistan that has not yet experienced the Soviet invasion or the Taliban takeover. You show a very traditional country that was beginning to open up to progress and westernisation. But resistance persisted, particularly in the countryside. You felt this tension but the authorities wouldn’t allow you to film what might appear to be a remnant of the past. Did you feel that you were often breaking the rules? Were there any risks involved?

Most of the time, they didn’t care what I was shooting. I could film anything I wanted. But there was a block on certain aspects of society that they didn’t want me to film because they felt it should no longer exist. And if they decided that it shouldn’t exist any more, then it didn’t exist for good. One of these points of contention concerned women who wore long veils covering their whole bodies. The government had banned the wearing of these full veils. The rule was followed by some women in the big cities and completely ignored in the countryside where husbands forced their wives to wear them. I knew that they didn’t like it and that they didn’t want me to film it, but I didn’t know how to avoid it, because itw as a street scene where there were a lot of people. But in the end I rather liked it. As I said in the film, it’s more interesting and more cinematic to show women with these long oriental veils on screen. We were dealing with two ways of life that didn’t understand each other. The Afghans were trying to become as modern as possible, but they still had a long way to go.

As far as the risks were concerned, if the authorities had come to me and said “don’t film that”, I wouldn’t have done it, it would have given me an excuse. I depended on them just as they depended on me. They wanted me not to break rules. And on the whole I did follow them. There were only one or two things they didn’t like, which I didn’t think were very important. For example, I filmed young boys playing with goat heads in the river. I didn’t see what was so terrible about that and I didn’t understand why I shouldn’t show it. The demolition of the mosque, which was in ruins, was also a sensitive point: they were destroying it so that they could build a new, bigger one. The Afghans forbade me to film this so as not to give Pakistan, their great enemy, the opportunity to say: “You see, they demolish mosques, they are not good Muslims, they are infidels”. Despite everything, I filmed in secret. Admittedly, I shouldn’t have done it, but I did anyway and I’m glad I did, because it produced some very beautiful images.

- You expressed your disappointment at not having been able to find any historical heritage in Kabul, or any monuments apart from the Buddha statue. Wasn’t this rather beneficial, as you focused on the people?

There was nothing there at all! But even when I was in India, I concentrated on the people and their activities, whereas there are a plethora of magnificent buildings in Delhi. But in Afghanistan, there was nothing like that. It was quite frustrating from that point of view. So I ‘hung on’, so to speak, to the Buddha statues. I couldn’t foresee that these thousand-year-old sculptures would be destroyed forty years later. It’s very moving in retrospect.

- Throughout the film, we are guided by the Mughal emperor Babur, who conquered Afghanistan in the 16th century and whose memoirs you use to illustrate your words and images. You show him as a sensitive, endearing, almost fragile character. Did you feel a certain closeness to him, particularly in the feelings he had for a young Afghan, Baburi?

Not fragile, no, I wouldn’t say that. Babur founded his empire at the age of fourteen. By the time he was seventeen or eighteen, so very young, he had already invaded and conquered India. He became the first Mughal emperor. He also went to Afghanistan, which he annexed. And all the while, he was writing his memoirs, probably the first autobiographical writings in history, describing his thoughts, his moods, his hopes, his regrets… He would never have imagined that such a work would one day be published and read by the general public, but that’s exactly what happened. As he grew older, his writings became less personal, containing more accounts of battles, the conquest of new territories and political reasoning. I feel a certain empathy for him, perhaps particularly in view of the feelings he had for this Baburi, whose name was curiously similar to his own. At the time of shooting, I wasn’t aware of all this background. I hadn’t read his memoirs. I didn’t find out about it until much later, even quite recently. That’s when I discovered a sensitive man who was homesick and melancholy. He loved Afghanistan and Kabul very much, as you can see in the film. For example, when someone brought him an Afghan melon to comfort him, he cried because it reminded him too much of his happy days. It’s a very moving thing.

- For Babur, travelling gives life meaning. For you too, because you opened yourself up to new cultures in Asia and travelled halfway around the world to film. Is this a parallel story of initiation, five centuries apart?

As Babur himself says, you have to get out of your comfort zone and do something with your life. That’s how you become someone. This is still true today. I had to go to Afghanistan to discover myself and find out who I was. It was the first major trip I ever made and it changed my way of seeing things, all my certainties. It gave me a taste for great excursions and I travelled a lot after that, including to Paris!

- It was also an introduction to love, but also to being forbidden and excluded because you were gay. In the 50s, you couldn’t openly show your feelings for your school friend. Babur may have repressed his true nature, like you at school, as you show it in the film.

I don’t think there was any such nature in him. As he said, he had never felt desire for anyone, including his wife, before he met this young boy. So he didn’t know that he had this capacity to feel love. But I wouldn’t call it a repressed nature, because that’s a modern idea. I prefer to talk about a feeling of attraction towards another person, which has materialised.

- Another recurring figure in your cinema, in addition to Merchant and Jhabvala, is Edward Forster, one of your main sources of inspiration, who is also featured here. To what extent did he introduce you to Kabul, and can it be said that you also became a filmmaker through literature?

No, I was a filmmaker long before that. He had written a very famous novel about India, called Passage to India. I read this novel as soon as I became interested in India. That’s how I came to know E.M. Forster. But his work wasn’t particularly important to me at the time; I didn’t know his other novels and they didn’t interest me much. It was only much later that I became aware of his literature through Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, whose favourite writer Forster was and whose writings she adored. It was then that I began to immerse myself in the other novels, which I later adapted: Room with a View, Howards End, Maurice… I’m going to tell you an anecdote, which I don’t often share. A number of filmmakers wanted to adapt Passage to India for the screen and asked Forster if they could obtain the rights to the novel, including the great Indian director Satyajit Ray. Ray visited the novelist in Cambridge; he had brought his films with him to show him his talents. Forster liked them and the two got on well, but in the end he decided not to sign over the rights, at least not during his lifetime. Ray returned to India and never made the film. After Forster’s death, Ismail Merchant and I were approached by King’s College, which was Forster’s legatee and executor. King’s representatives invited us to visit them in Cambridge. We knew exactly what they were going to offer us: an adaptation of Passage to India. That’s what happened; as soon as we arrived, they offered us the rights. But we turned them down because we had a lot of other projects lined up and we told them that what we really wanted to do was make Room with a View, another Forster novel. They were stunned: “What do you mean? A Room with a View? This little comic novel? You’d rather adapt that than the classic Passage to India?” We confirmed our choice and they ended up giving us the rights. We went on to work with them on two other occasions: the adaptation of Maurice and, in 1991, Howards End.

- And Passage to India was finally adapted by David Lean in 1984. It was actually his last film. What did you think of it?

I didn’t like it, any more than I liked the personality of David Lean himself, whom I met on several occasions, in India and elsewhere. He was exactly the kind of Englishman that Forster hated: he stomped, he shouted… He was also the kind of man that Forster felt should never have got involved in India, or else he would have made terrible mistakes. You see these people in Forster’s novels, like Howards End. One of the characters in my film, Mr Wilcox, played by Anthony Hopkins, could have been Lean. Or to be more precise, David Lean could have played Mr Wilcox to perfection. So Lean and Forster were not people who were destined to get along and see things the same way. If anything, they were radical opposites.

- By the way, he too has made a film about Venice, contemporary with yours, but which is fiction: Summertime.

I actually rather liked this one. I made my film about Venice in 1953 and he made his in 1955. I was particularly happy to see Venice filmed from this angle, even if, at the time, certain elements that I thought were wrong offended me, such as the layout of the buildings along the Grand Canal, which we see in his film from a gondola. In the editing, he had completely altered the appearance of the city by showing a building that should never have been there in the first place. I thought that was dishonest. If you film Venice, or any other city that really exists, you have a duty to photograph it exactly as you see it, without changing anything, otherwise it loses its authenticity. That was my way of thinking and conceiving a film at the time. That said, as I’ve got older, I’ve had to resign myself to reproducing exactly the same thing I was criticising a few years before, largely for aesthetic and practical reasons. If you can achieve a more beautiful result by cheating reality a little, what’s the harm? You give free rein to your imagination and your sense of beauty and aesthetics. That’s the artist’s freedom.

- You’ve made a number of films about British society in the 20th century, particularly in the era of Edward VII. You may have been mistaken for a British filmmaker, but you are American and you make that clear here. What is your relationship with the country of your birth?

I’ve made a lot of typically American films, notwithstanding. I’ve always lived in America, never abroad, except on location, whether in Paris for a while, or in London, India, South America, China and so on. But I always ended up back home in New York. I’ve never felt expatriated in America. Born in California, I moved to Oregon with my family when I was very young. At that time I was the little boy you see in the film. I spent my childhood and adolescence there, then went off to university and followed my family back to California. Incidentally, as I say in the film, some of the landscapes in Afghanistan reminded me of those in Arizona or Colorado, because of their similar topography and because they are the same colour red. A sign that I’ve never really left America.

- To conclude, do you have any other films hidden away in your archives that might one day be rediscovered?

No, it’s over, there’s no more. I really enjoyed editing this film. It was a really fun experience. I didn’t really know what Giles was up to: he had a lot of things in mind about what he was going to do that I wasn’t aware of at the start. And little by little, everything fell into place. But now I don’t really have any other projects, I’m too old. Maybe memoirs? Who knows…

- James Ivory & Giles Gardner, Un été afghan, 2022, propos de James Ivory recueillis par Guillaume Narguet

Crédit photo : James Ivory © Jean-Philippe Marier